How Rep. Phillip Burton and a Magic Marker Hijacked Tomales Bay into the Golden Gate National Recreation Area

George Clyde

I have a home in the town of Marshall. The town is a strip of about thirty-five homes and businesses along Highway One on the east shore of Tomales Bay, in the rural unincorporated area of west Marin County, near Point Reyes. About fifty people live in Marshall, mostly in small cottages at the edge of the bay.

Tomales Bay is approximately ten miles long and averages a mile in width, sitting directly atop the San Andreas Fault. One of the most pristine estuaries in the world, the bay is home to the famous Hog Island Oyster Company, which grows shellfish in its waters.

Marshall is greatly loved by those of us who live there and by the tourists who enjoy the scenery and the oysters. But it is not of much national importance. So I was surprised to learn that in 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed a law adding this sentence to the laws of the United States:

For the purposes of this subchapter, the southern end of the town of Marshall shall be considered to be the Marshall Boat Works.

You might wonder, Why did Congress enact a federal law to define the southern end of the town of Marshall? It’s a good question, especially since there is no other reference to the town of Marshall or the Marshall Boat Works in that subchapter or in any of the other laws or regulations of the United States.

The law was part of 1980 legislation expanding the boundary of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. When I asked senior officials and rangers at that national park to explain the reference to Marshall and what it means, they had no idea. It was a complete mystery to them.

I came across this little mystery when I was trying to solve a bigger one—what is the legal boundary of the GGNRA, and does it include Tomales Bay? That question is important to me because my home rests on stilts above the bay and I have a mooring on the bay. Do park laws apply to me or not? And the question is important to boaters, to kayakers, and to the park, whose rangers cruise the bay in patrol boats enforcing park regulations.

As a retired lawyer, I decided to look at the 1980 law that established the park’s northern boundary. That simple research project tumbled me into the fast-and-loose world of the late California Congressman Phillip Burton, where I learned an astounding secret about the park boundary and Tomales Bay.

GGNRA map dated December 28, 1980 showing Tomales Bay to be within the boundary of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Map Courtesy of GGNRA archives

Phillip Burton and a Missing Map

Burton served in the House of Representatives from 1964 until his death in 1983 at age fifty-six. His passion for the environment, his pursuit of power, and his unorthodox maneuvering helped put millions of acres of wilderness and park properties under federal protection. But his laws had a few rough edges—like the peculiar reference to the town of Marshall. And, as I learned, Burton, too, had a few rough edges.

“Nobody is perfect—certainly not the late Phillip Burton,” California historian Kevin Starr wrote in a comment on John Jacobs’s book, A Rage for Justice: The Passion and Politics of Phillip Burton. Starr went on, “Congressman Burton loved power and pursued it egregiously. He had a terrible temper. He was sometimes hasty and imprudent. Yet he was also a great legislator: great in his vision, great in his defense of working people, great in his passion for the environment. Few members of Congress have wielded his influence or left behind the legacy of this towering, tumultuous parliamentarian.”

In my research, I discovered how Burton wielded his influence to bypass the law.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, spurred on by local environmentalists, Burton aggressively pursued expanding the GGNRA boundary to include properties that were still undeveloped. The federal government would acquire these properties for the park and protect them from development for vacation homes and tourist businesses.

As a result of Burton’s efforts, President Carter signed the 1980 law expanding the national park boundary. According to the law, the boundary is shown on a map entitled “Point Reyes & GGNRA Amendments, October 25, 1979.” So the map would show whether Tomales Bay is within the park boundary or not.

But the map was missing. It should have been on file at the Department of Interior’s Washington headquarters, but it was not. Nobody knew where the map was or what had become of it. Some doubted the map ever existed. The law requires that the map be on file and available for public inspection at National Park Service headquarters in Washington. I placed a number of calls to park service officials in Washington only to learn that they did not have the map there. Nor could they find any record of ever having received it.

Surely, I thought, someone had to have a copy of the official map that Congress adopted to describe a national park. A simple telephone call to the right person in the right office should end the search.

The Washington staff suggested I check with the Park Service’s Harpers Ferry Center in West Virginia, which designs NPS maps for publication. That office also had no knowledge of the map; they sent me to the NPS Denver Service Center, the federal agency’s repository for maps.

Until that point, I had been looking for the map quite informally. But the Denver office considered my simple request for a copy of the 1979 map a Freedom of Information Act filing. Unexpectedly, my search had become official government business. The FOIA request launched a cascade of formal searches that extended to the park service’s Western Regional Office in Oakland, to the GGNRA headquarters in San Francisco, and to the GGNRA archives in the San Francisco Presidio.

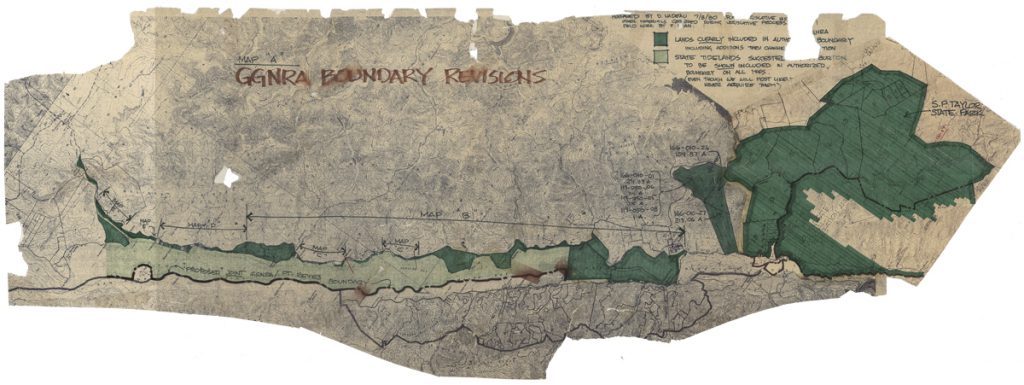

Damaged map entitled “GGNRA Boundary Revisions,” dated July 8, 1980, found by the author at the GGNRA archives. Map Courtesy of GGNRA archives

Madly Searching for the Missing Map

“We have practically the entire NPS searching for the maps and have pretty much come to the conclusion that they don’t exist!” wrote Susan Ewing Haley, GGNRA park archivist, in an email that went to ten current and former park service employees involved in the Freedom of Information Act search for the map.

As a lawyer, I was astonished. How could Congress pass a law for a national park and refer to a map that did not exist? But Susan Ewing Haley’s startling conclusion was echoed by the Park Service’s real estate staff—officials who needed to know the park’s exact legal boundary. Greg Gress, Chief of the Land Resources Program at the NPS regional office, wrote me in an email: “Regarding the GGNRA/Pt. Reyes map, what I’m suggesting is that, despite what the law said, the map was never created and therefore isn’t on file here or in DC. I’ll double check next week with our cartographer to make sure about this, but if it’s the map I’m thinking of, it just doesn’t exist, or if it ever did exist, it has been lost both here, at the Park, and in DC.”

The skepticism within the agency only spurred me on.

A break in my investigation came during the Freedom of Information Act search when the Park Service consulted Douglass Nadeau, former Chief of the GGNRA Division of Resource Management and Planning. Nadeau was Burton’s primary contact at the park during the 1980 boundary expansion. Now retired, he shed light on how Rep. Burton handled legislation in those days and provided hints about what may have happened to the map. He wrote in an email:

Every time Phil Burton was inclined to expand our boundaries he asked me to prepare a down-and-dirty map outlining the proposal according to his directions…with the proposed additions and text depicted with Magic Markers. They were usually dated by me and signed by Phil. These were the maps that were referenced in the new legislation—very unconventional but it was the way he wanted it.

To correct this irregularity, the Denver Service Center should have followed up with an official, numbered, reproducible map. My sense is that in most cases this did not happen.

If any of those original maps made their way back to my office, they are in the [GGNRA] archives.

Unfortunately, I seem to recall a conversation with Bill Thomas or one of Phil’s aides when they said that the last time they saw those maps they were rolled up on the floor under a couch in Phil’s office! I wish I could offer a more promising lead.

It now seemed likely that the 1979 map probably did exist in some form at some time. And Nadeau’s email had all but confirmed something else: it was he who created the elusive map. Moreover, the map, if I were to find it, would be hand-drawn with Magic Markers.

Contributors

Many talented individuals are featured in the West Marin Review. Please click below for this volume’s contributors.

- COVER

- Marnie Spencer Gullible’s Travels

- PROSE

- Alvin Duskin Uncle Dave

- Joan Thornton Gretel

- Francesca Preston Creating an Apian Society

- Michael Parmeley Jake’s Memorial

- Jody Farrell Cutting the Boys’ Hair

- Frances Lefkowitz Something Severe

- Susan Trott About Bunin

- F. J. Seidner Collecting

- George Clyde How Rep. Phillip Burton and a Magic Marker Hijacked Tomales Bay

- Mark Dowie Kitchen Tables

- Carola DeRooy The Language of Baskets

- William Masters Etiquette

- POETRY

- Robert Hass Planh or Dirge for Those Who Die in Their Thirties

- Joan Thornton A Taste for Action

- Glen Stephens You and I and Two Bottles of Beer

- Nancy Binzen I Know Three Things

- Gina Cloud covenant

- Emily Cardwell Sponge

- Lisandro Gutierrez Plants and the Water

- Monte Merrick untitled, loss and what comes next

- Helen Wickes The Year My Nouns Left Town

- Calvin Ahlgren Refurbishment: Rain on the Way

- Gary Thorp Flight Plan

- Claudia Chapline Selection from One Stroke One Breath

- Jacoba Charles Inverness Summer

- Margaret Chula Dystopia

- Donald Bacon Quail Fog

- Jane Hirshfield Many-Roofed Building in Moonlight

- A. Van Gorden Fact

- ART + ARTIFACT

- Carolyn Means Red Glow: Wood-Fired Tea Bowl

- Susan Hall Old Cypress

- Kaya Gately Hummingbird

- Cynthia Pantoja Serenity

- Thomas D. Joseph Bodega Bay, Autumn

- Patricia Thomas She Lived in Two Worlds; She Lived in Two Worlds (Negative)

- Kathleen Rose Smith Sun Woman Triptych

- Jon Langdon Night Rose

- Susan Preston Lou’s and Francesca’s First Hive

- Amanda Tomlin Memorial (Our Lady of the Harbor by David Best)

- Jonathan Aguilar I Try

- Hector Martinez #1 Pride

- Olivia Fisher-Smith Submerged

- Leslie K. Allen Limantour Estero, Pt. Reyes, No. 2 (Dune Grass)

- Candace Loheed Birds of a Feather

- Claudia Chapline Four Calligraphic Images

- Mardi Wood Maremma Bull

- Pam Fabry The Shape of Things

- Salihah Moore Kirby spirits on the afternoon ship awake from an important nap-dream

- Marnie Spencer Gullible’s Travels

- Jan Langdon Red, White and Black

- Shirley Salzman Looking North from Millerton

- Christa Burgoyne Pt. Reyes Barn #1/#2 and Raven, Body Feather

- Eileen Puppo In the Valley

- Russell Chatham Looking Toward the Absarokas

- Sabine (Bree) Terrell The Birds’ Song

- Austin Granger Tomales Bay

- Artist Unknown Coast Miwok Basket

- Toni Littlejohn The Lioness

- Francesca Preston Irises and Paper

- Rutilio Plasencia Arbol de la obscuridad

- Igor Sazevich Olema

- Mary Curtis Ratcliff Waterweb

- Christine DeCamp Spring Fog

- Tomales High School Art Students West Marin Review Posters

- MUSIC

- Bart Hopkin Call Dynah