Tom Killion on Mount Tam

Steve Heilig

I first met Tom in the 1960s, and he had given me a gift of his early book, Views of Mt. Tamalpais. He’d become a passionate print artist fairly early on. After some years he got hold of me to do a book on the high Sierra, which was a wonderful project. And after several more years he said he’d like to do another on Mount Tam, and I was interested from the start.

—Gary Snyder, poet and co-author, with Tom Killion, of Tamalpais Walking

Mount Tamalpais is Marin’s Mount Everest. Although only 2,574 feet high at its summit, it dominates the county; to get to or from West Marin from almost anywhere else, you have to go over or around it. Much has been written about “Tam,” and countless photographs have been taken and published featuring its image. However, what may prove to be the ultimate book about Tam does not feature a single photograph. Tamalpais Walking: Poetry, History, and Prints, published by Berkeley publisher Heyday Books in 2009, is a labor of love featuring 60 of Tom Killion’s singular prints, done over decades and providing viewpoints from vantages all over the mountain and from all over Marin and the Bay Area.

Tom grew up in Mill Valley and recalls feeling awe since early childhood toward Mount Tam towering over the town. His first memory of the mountain, he recalls, was “when I was about seven, and went way up on the fire roads with my next-door neighbor’s family, and discovered I could just go right out our back door and up some flights of steps and be on the trails—it was a real adventure.”

Tom liked history and took a doctorate in African history at Stanford. He has traveled the world. He found a home in Inverness Park with three other families in 1988 but didn’t move there until 2003, when he built the studio where he produces, in his immediately recognizable style, scores of colorful woodblock prints of natural landscapes. He’s interested in accuracy, and he doesn’t much care for the story that Native Americans saw a “sleeping lady” in the contours of Mount Tamalpais. He explains:

It’s an invention, one of the nineteenth-century creations of the new settlers. As the Europeans took over new parts of America, they seemed to want to create some sort of back story for themselves. And what they did was foist it upon the people they’d displaced. Here at least it is relatively benign. The “Sleeping Beauty” story was quite popular in the mid-1800s, as the Brothers Grimm had just published their collection of fairy tales, and then out came some operas, such as Wagner’s Ring Cycle. Germans were the biggest population group of immigrants in the Bay Area in the late nineteenth century, and they loved to go hiking. They pioneered the hiking culture on the mountain.

The first mention in writing of the Sleeping Maiden or Sleeping Lady dates to the 1870s, Killion says. The idea that Miwok Indians named her came later.

To make it seem more authentic, the first generation of kids born and raised in Marin and San Francisco in the late 1880s and early 1900s started to put it into poetry and such. Most of them had read “Hiawatha” in school, and there were all sorts of invented Indian legends then. They couldn’t quite decide how to view the Native Americans here, for as long as they were still contesting them for the land they hated them and it was massacres and genocide, but once the Indians were subdued and disappeared into the background, they became “noble savages.”

Killion says it is not surprising that no mention of a sleeping maiden has been found in Native American lore, and certainly not among Marin’s Miwok people:

You just don’t find that kind of anthropomorphizing of places around here. People I’ve talked to who are descendants of Miwoks say it was all invented. The fascinating thing is how young people in the early twentieth century, already a generation removed from the days when there was much interaction between Miwok people and the early settlers, wanted this mountain they loved to have a romantic past. So they came up with these wonderful adolescent stories—and the adults grabbed hold of them and used them to create a romantic background for their culture of hiking. The myth was the centerpiece of the drama “Tamalpa,” the first of the Mountain Play open-air productions staged on Mount Tam in 1921.

Of course, once somebody points out the maiden’s profile, you can really see it. It is actually more noticeable from farther away, either north or south—especially from Black Point [in Novato] and the East Bay. I think the first Europeans to notice it were probably the gold miners who traveled by paddle wheeler from the City up the Bay to the Delta, because all along that trip the maiden’s outline is quite noticeable—and everyone knows how few women they had with them.

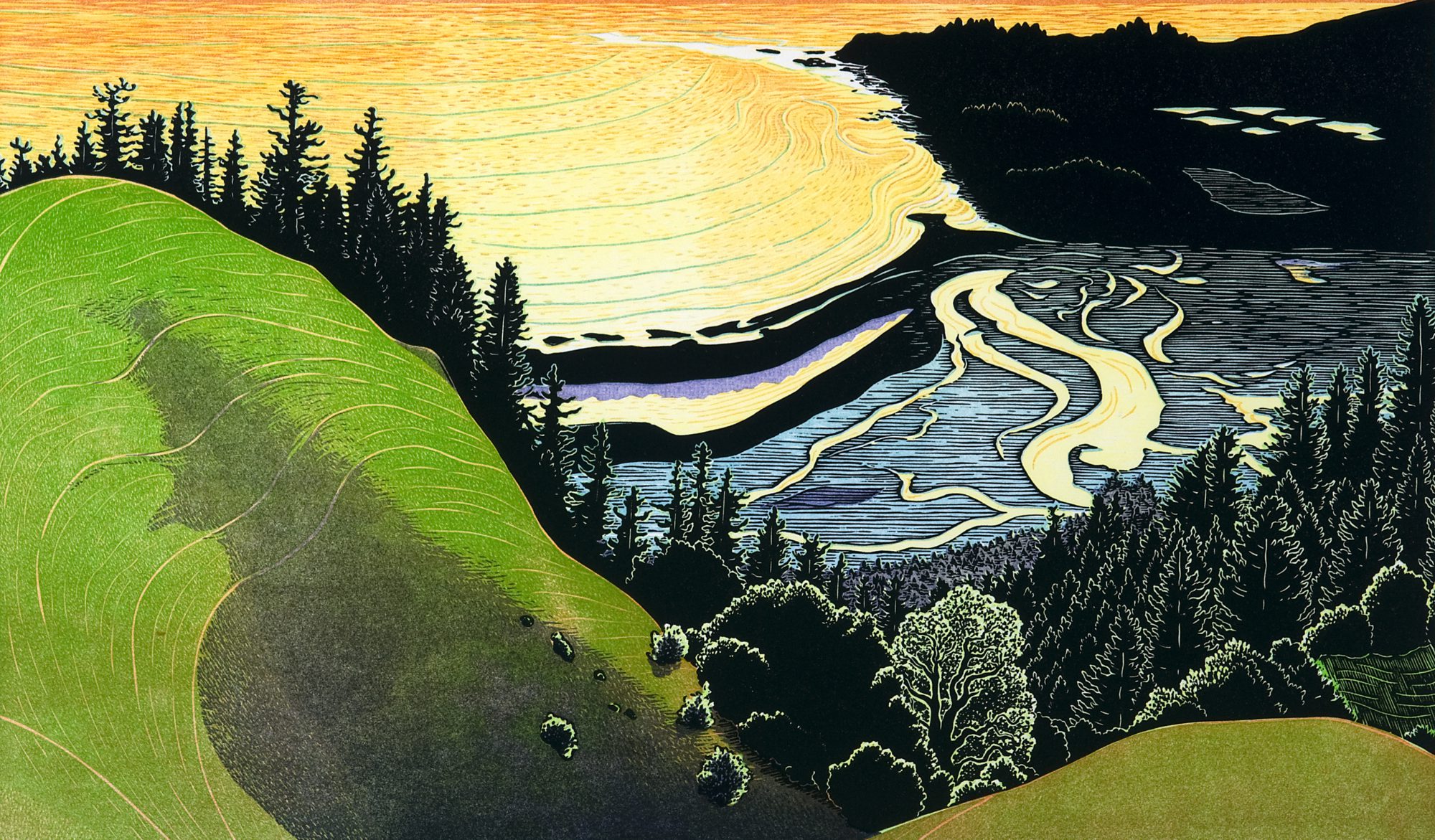

Tom Killion, Mount Tamalpais from Big Rock Ridge

Killion never took any art classes. His earliest woodcut of Tam dates from 1969 or 1970, done when he was a teenager as a holiday card for his family. Today his more elaborate pieces have many layers of color, and a single image can take him more than three hundred hours to produce. “I tend to expect that I’ll spend two months on something, but it often runs to almost four months for these big color pieces.”

Killion begins his prints by reversing the lines of one of his many field sketches onto a wood or linoleum block. “I never work from photos. You can’t really see the lines of the landscape in color photos the way you can in reality. So I do my sketches in the field, usually in pencil or ballpoint pen, with notes scribbled in about vegetation, light, and colors.”

This first block becomes Killion’s “key block,” which contains the outlines for successive color blocks. When he has finished the key block he transfers the image from it to as many color blocks (usually made of Japanese shina wood) as he thinks he will need for his print. Some prints only have one or two color blocks, others have six or seven, which Killion then expands into as many as fifteen or more color “layers” by sawing some of the blocks into pieces and printing the sections separately with different colors, or by doing “reduction cuts” on the blocks, printing the color block once in a lighter color, then carving it away some more and printing it again with a darker inking. Using semi-transparent inks and “gradated rolls” with the rubber inking rollers on his hand press, Killion can produce a dazzling variety of colors and “fade” effects, such as the Japanese-style bokashi fades from light to dark in sky or water. This all takes a great commitment in time and patience.

Sketching is the quickest and most immediate part of the process. Then from those hundreds of sketches I eventually choose one to put all the hours of labor into, finally producing a print. Carving the blocks, particularly the key block, is the most time-consuming part of the process, but perhaps the part I enjoy the most. I use Japanese hand tools—“V” and “U” gouges—which must constantly be sharpened. But I love watching the landscape, with all its marking for rocks and vegetation, take shape in low relief on the block’s surface.

Then there’s the printing, a day for each color layer. What I never tire of in the process is the way the print takes on a life of its own. This is the great joy of printmaking, its magic and its mystery, that in the end, no matter how much I try to plan it, the image comes out as it will, not exactly as I envisioned it. Sometimes it is thrilling, often it is initially disappointing—as it is not what I had planned to do at the beginning of the process—but then it grows on me, and a week later, when I look at it again, I love it.

These are Tom Killion’s favorite spots on Mount Tam:

Out at the serpentine power point above Rock Spring, and down along the front of Bolinas Ridge, almost any old place there, and an area over on the north-side trail where you have this wonderful forest of madrones with beautiful pink bark mixed with California nutmeg in amongst that bluish graywacke rock that is all over Mt. Tam.

Also Lone Tree Spring, on the Dipsea trail—I’m sure that’s what Lew Welch was thinking of when he wrote his “Prayer to a Mountain Spring”:

Gentle Goddess

Who never asks for anything at all,

and gives us everything we have,

thank you for this sweet water,

and your fragrance…*And of course the Steep Ravine trail with its ferny cliffs and moss-covered staircases; the Bootjack trail down to Muir Woods with its creekside azaleas and footbridges; the grassy hillsides above Cataract Creek waterfall, and so many more.

*Lew Welch, from Ring Of Bone: Collected Poems 1950–1971 (Edited by Donald Allen. Grey Fox Press, 1979)

Contributors

Many talented individuals are featured in the West Marin Review. Please click below for this volume’s contributors.

- Cover

- Tom Killion Bolinas Ridge Sunset

- Prose

- Catherine David Amateurs Are First-Rate Lovers

- Reynold Junker Yesterday, Perhaps

- Jessica O’Dwyer Meeting Ana

- Agustina Martinez Life in Mexico

- Jan Harper Haines Hootlani!

- Agnes Wolohan Smuda von Burkleo Fall

- Vivian Olds Marin Memoirs

- Elia Haworth Farming and Ranching in Bolinas 1834 to 2010

- Jonathan Rowe Fellow Conservatives

- Steve Heilig Tom Killion on Mount Tam

- Daniel Potts Scattered Threads

- Flor Jimenez Broken Blood

- Jazmine Collazo Good-bye, Hello

- Cynthia A. Cady The Miles Pilot

- Jody Farrell The Cat Lover

- Dave Mitchell Tall Tales of Intelligent Animals

- Terry Nordbye If Two-by-Fours Could Talk

- Poetry

- Jodie Appell Advice for the Marin Lovelorn

- Prartho Sereno The Dancing Cure

- Julia Bartlett Dinner Down the Road

- Gillian Wegener After Dry Lightning

- Juan Avalos Dear Mud

- Albert Flynn DeSilver Hope

- Lynne Knight Apology, with Hawks Veering

- Randall Potts A Natural History

- Hal Ober Camellia and Chameleon

- Roy Mash I Was Getting Ready To Tie My Tie When

- Nellie Hill Winter Horse

- Art + Artifact

- Patti Trimble Endangered Mission Blue

- Nell Melcher Dark Trees

- Ryan Giammona Quail

- Andrzej Michael Karwacki Art Natura 03 and Little Voices of Flowers

- Amanda Tomlin Nicasio Reservoir Thistles and First Rain, White House Pool

- Kurt Lai Path

- Jessica Baldwin Spring Lamb

- Willow Dawson Hummingbird

- Sha Sha Higby In Folds of Tea/Dance in Sculptural Costume

- Marnie Spencer Wish You Were Here

- Terrence Murphy Summer and Fence Mender

- Christa Burgoyne Fuller’s Teasel

- Wendy Goldberg Meadow: West Marin

- Dewey Livingston West Marin Portraiture: Photography by Seth Wood, 1940s to 1950s

- Tom Killion Bolinas Ridge Sunset and Mount Tamalpais from Big Rock Ridge

- Richard Lindenberg Inverness Marsh West

- Lorna Stevens Herd

- Kevin Alvarado Untitled

- Jacqueline Mallegni Sky Barge

- Christin Coy January Afternoon—Bolinas Lagoon

- Kyla Pasternak Jenna

- Mary Siedman Lively Peony and Bolinas Lagoon

- Zea Morvitz Four Prepared Books

- Vi©kisa A Dog’s Life

- Jon Langdon My Matilijas

- Mark Ropers Shades of Red

- Sevilla Granger Marin West; Marin East and Santa Barbara 101

- Mardi Wood Horse