Fellow Conservatives

Jonathan Rowe

Out here on the edge of the continent, where the force fields of respectability and convention run thin, we like to think of ourselves as progressive, in an undogmatic way. But really we are conservative, when you get down to it. We are alert constantly to the capacity for evil in human nature, especially in the form of greed, and greed’s designs upon the land. We are skeptical of the version of progress that the corporate market pushes at us. We embrace the wisdom of the past, especially as embodied in the natives of this place.

Russell Kirk, the intellectual progenitor of modern conservative thought, marked these as central tendencies of what he called the “conservative mind.” (Kirk would not be pleased by what claims that banner today, but that’s another matter.) We revere the land and take a dim view of change, and if those are not conservative inclinations, then nothing is.

Unlike the conservatism that prevails in Washington, ours is not pliant to moneyed interest or calculated for political advantage. It represents the strange fate that befalls the progressive in a commercial culture that turns everything into a commodity for gain. Yet this does not exempt us from the karmic conundrums that attend efforts to resist change or turn back the clock. Nor does it make us immune to the blind spots that can occur when a sense of virtue is wrapped up too tightly in the preservation of a status quo, even an ecological one.

Create a national park, restore a wetland, and people want to drive out here to partake of them. Start to create a local food economy, and more people come who are less interested in the landscape than in the food. The town fills with cars. Parking becomes a problem. A place in which ecology is practically a religion becomes, on summer weekends, a hot spot on air pollution maps.

We locals become a little cranky and walk around with a debate inside our heads. We like our neighbors who have started the ventures that help attract these crowds. We want them to succeed. We support local economy, organic food, all of it. Yet each success takes us a little further from what we thought we wanted to be—or at least from what this place used to be. It also drives up real estate prices, so that people who made the community what it is can no longer afford to be part of it.

It is not a new dilemma—the failure of success. But it has a particular and ironic twist in a place where people thought they were going to be different. It eats at us, the way our certitudes keep colliding; and this is what makes local points of contention—a footbridge over a creek, or an oyster farm on Tomales Bay—so symbolically hyper-charged, almost like conflicts in the Middle East. The disagreements are over competing versions of good and therefore become projection screens for the tensions that beset us not just from the outside, but from inside as well.

Walking—good. Sustainable aquaculture—good. Local food economy—good. How do such goods become bads? It is hard enough to battle developers. Now the fight is over objects of our own desire too. We feel a need to draw a line. But where, and how—especially when we are part of what we have to draw the line against?

We build our homes at the edge of this stunning landscape—well, let’s call the spade here, in this stunning landscape. Then we get our backs up at those who would intrude upon it with their footsteps, or a sustainable livelihood, or a second unit that enables the owner to afford the first. We create our own understated and ecologically responsible versions of better homes and gardens, and then wonder why the town cannot remain forever the rough-edged remnant of the Old West it still is in our minds.

As somebody once put it, the one who builds the house is the developer; the one who lives in it is the environmentalist. Yet we are not unself-conscious people. The paradoxes—I put this gently—of our oppositions rest uneasily in us, along with the awareness that we are a privileged group to begin with—we who oppose privilege on principle—just for being here. We find ourselves a little like those people who, in middle age, begin to suspect that they have become the parent they rebelled against, and that their rebellion somehow binds them to that parent all the more.

This quandary is not new to me. From the time I first came to West Marin 15 years ago, I have felt that I had walked back into a drama I’ve been through before. I spent my teen years at the tip of Cape Cod, which is as far east as Point Reyes Station is west. My mother’s husband was an artist-craftsman who owned a shop—and later apartments—in Provincetown, where the land ends, and from which the next stop is England. The Pilgrims landed there before they went on to Plymouth.

P’town, as it is called, is a compact little village along a narrow strip between the bay and the dunes. Physically and geographically, it is very different from West Marin. The Cape at that point is less than two miles wide; the open spaces are out to sea. History overhangs the place in the form of a tower that commemorates the Pilgrim landing.

And yet P’town in those days was similar too. The traditional economy was based on food. Where we have cows, P’town had fish. More precisely, it had a fishing fleet that worked the bay and the Georges Banks beyond. The old-timers were Portuguese fishermen, tough, swarthy guys who went out for a week or more and who still walked barefoot down Commercial Street in winter. As out here, there were decaying remnants of a railroad. It had once carried the fish to Boston, which is 120 miles by land, though only about 50 by sea.

What P’town shared most with West Marin was a sense of being beyond the pull of social constraint. It was a separate world; you could go for years without a coat and tie. Artists and writers were drawn to the rustic authenticity where they were close enough to Boston and New York for a quick visit to a publisher or gallery. Eugene O’Neill started the Provincetown Playhouse. Norman Mailer, Stanley Kunitz, and a host of others followed.

What drew them drew another group as well—gays, who came in summer droves and let it all hang out in ways they couldn’t even in New York back then. The result was a mélange like no place else. There was traditional P’town, embodied in the fishing fleet and Portuguese Bakery, with its flipper bread and tangy soup. And then there was Mr. Kenneth with his hat shop; the female impersonator lounge singer at the Crown and Anchor Inn; the lesbian bar called the Ace of Spades, which jutted out into the bay and from the deck of which throaty laughter could be heard late into the night; and the Atlantic House down the alley where the homo-erotica in the men’s room could make even a gay sailor blush. A town council dominated by people with names like Santos and Cabral looked upon it all with a Mediterranean shrug. (The business brought to their bars and restaurants didn’t hurt.)

It was a rich mix, and a fragile one. As with so many places, P’town was done in by what made it so attractive; its uniqueness turned on itself. The tourist shops metastasized. Fudge became more prevalent than fish. The gay self-presentation became more circus-y and contrived. Wooden cottages were spiffed up. Rough turned into quaint; the nooks and crannies of affordability disappeared. The year-round population diminished; merchants had fewer customers in the winter months. Meanwhile, artists without trust funds could no longer pay the rents—nor could very many others.

If the shoe doesn’t fit enough already, there’s more. Outside of town, a new national park—the Cape Cod National Seashore—made the lower Cape (the end furthest out, though also the furthest north) all the more attractive, and the existing real estate all the more valuable. The park saved a precious landscape—within its boundaries. Outside them, development came like mange. The marsh across the road from the Goose Hummock outdoor shop in Orleans, which I passed on my way to school each day, is now the Cranberry Cove Plaza. You could be anywhere. Much of the Cape is that way now. It pains me to go back.

In the parts that aren’t spoiled, moreover, an Aunt Sally landscape has replaced the Huck Finn version—preserved, but with a precious quality, and woe to him or her who tracks dirt across the rug. Deer hunting season used to be a little like a Jewish holiday in New York, with empty desks at Nauset High School. Now the woods are houses. The guys go to New Hampshire to hunt. There was a dune colony just outside of P’town, near Pilgrim Lake, where adventuresome souls lived off the grid in summer in driftwood shacks. The Park Service took it down.

The dune colony was a little like the summer encampment at White House Pool, halfway between Point Reyes and Inverness, where young people in the 1960s took refuge when they had to relinquish their winter rentals to the owners. The informal campsite couldn’t happen now; and what is relief to some is a sense of loss to others, leaving us with a nagging question as to whether there might have been another way—one that maintained our rougher edges and the social dimension of our landscape.

Contributors

Many talented individuals are featured in the West Marin Review. Please click below for this volume’s contributors.

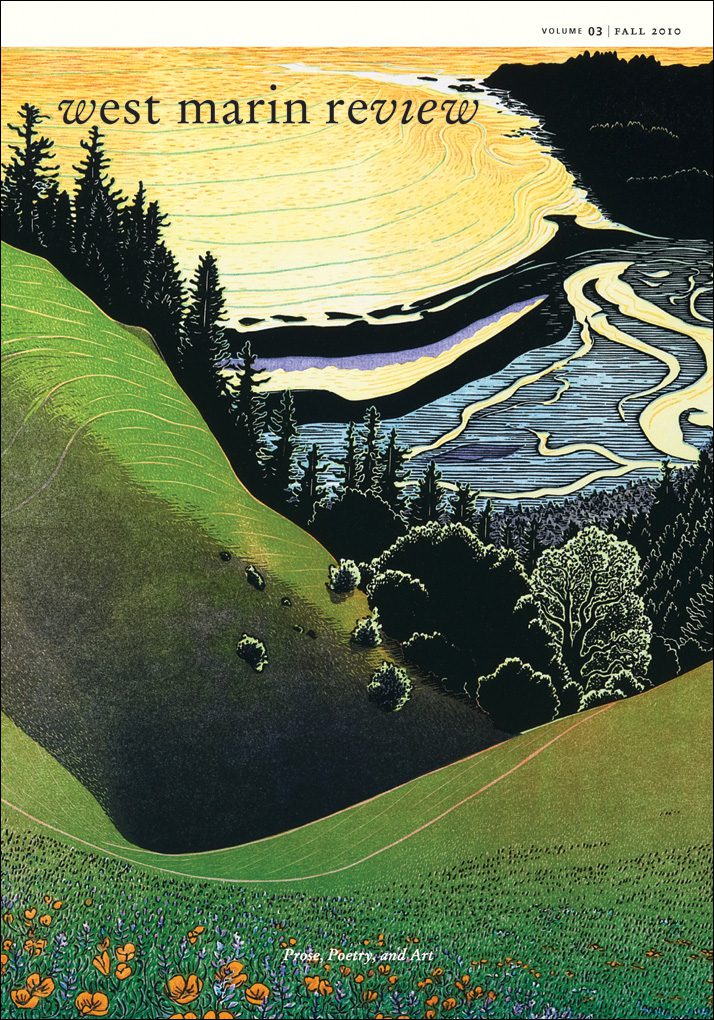

- Cover

- Tom Killion Bolinas Ridge Sunset

- Prose

- Catherine David Amateurs Are First-Rate Lovers

- Reynold Junker Yesterday, Perhaps

- Jessica O’Dwyer Meeting Ana

- Agustina Martinez Life in Mexico

- Jan Harper Haines Hootlani!

- Agnes Wolohan Smuda von Burkleo Fall

- Vivian Olds Marin Memoirs

- Elia Haworth Farming and Ranching in Bolinas 1834 to 2010

- Jonathan Rowe Fellow Conservatives

- Steve Heilig Tom Killion on Mount Tam

- Daniel Potts Scattered Threads

- Flor Jimenez Broken Blood

- Jazmine Collazo Good-bye, Hello

- Cynthia A. Cady The Miles Pilot

- Jody Farrell The Cat Lover

- Dave Mitchell Tall Tales of Intelligent Animals

- Terry Nordbye If Two-by-Fours Could Talk

- Poetry

- Jodie Appell Advice for the Marin Lovelorn

- Prartho Sereno The Dancing Cure

- Julia Bartlett Dinner Down the Road

- Gillian Wegener After Dry Lightning

- Juan Avalos Dear Mud

- Albert Flynn DeSilver Hope

- Lynne Knight Apology, with Hawks Veering

- Randall Potts A Natural History

- Hal Ober Camellia and Chameleon

- Roy Mash I Was Getting Ready To Tie My Tie When

- Nellie Hill Winter Horse

- Art + Artifact

- Patti Trimble Endangered Mission Blue

- Nell Melcher Dark Trees

- Ryan Giammona Quail

- Andrzej Michael Karwacki Art Natura 03 and Little Voices of Flowers

- Amanda Tomlin Nicasio Reservoir Thistles and First Rain, White House Pool

- Kurt Lai Path

- Jessica Baldwin Spring Lamb

- Willow Dawson Hummingbird

- Sha Sha Higby In Folds of Tea/Dance in Sculptural Costume

- Marnie Spencer Wish You Were Here

- Terrence Murphy Summer and Fence Mender

- Christa Burgoyne Fuller’s Teasel

- Wendy Goldberg Meadow: West Marin

- Dewey Livingston West Marin Portraiture: Photography by Seth Wood, 1940s to 1950s

- Tom Killion Bolinas Ridge Sunset and Mount Tamalpais from Big Rock Ridge

- Richard Lindenberg Inverness Marsh West

- Lorna Stevens Herd

- Kevin Alvarado Untitled

- Jacqueline Mallegni Sky Barge

- Christin Coy January Afternoon—Bolinas Lagoon

- Kyla Pasternak Jenna

- Mary Siedman Lively Peony and Bolinas Lagoon

- Zea Morvitz Four Prepared Books

- Vi©kisa A Dog’s Life

- Jon Langdon My Matilijas

- Mark Ropers Shades of Red

- Sevilla Granger Marin West; Marin East and Santa Barbara 101

- Mardi Wood Horse