The Prudent Man

Rick Bass

The indefatigable Cesar Hernandez is to the Cabinet Mountains and the rest of northwest Montana the shining spirit, the one link in a greater chain. Slender, wiry, alternately mercurial and thoughtful, Hernandez, a native of Puerto Rico, grew up in Brooklyn and moved to the secluded Cabinet-Yaak country almost forty years ago. He fought as a Marine in Vietnam and worked in the woods as a tree feller and miner. He’s an elk hunter and union organizer, but he has been unfairly reviled for years by loggers who have never met him but who have heard his fearful name.

Working for the Montana Wilderness Association as their sole field rep in northwest Montana, Cesar covered a territory the size of the state of West Virginia—Lincoln, Sanders, Flathead, and Lake counties—while reporting back to Helena, six and a half hours (one way) from the farthest reaches of his territory. He also spearheaded the drive to turn back one mine after another from the flanks of these slender, imperiled mountains: Noranda Mining on the east face, Asarco on the west face, and the proposed Fourth of July and Way-Up mines, in which individuals sought to drive a jeep through the wilderness (courtesy of the 1872 Mining Act) to access their claims.

One of the best Cesar stories is one of the oldest. More than thirty years ago, prospectors were planning to patent a claim up in the Scotchman Peaks country just over the border in Idaho—an 88,000-acre, unprotected roadless area and Cesar’s favorite place on Earth. A fellow activist, Cal Ryder, was sitting at his table having Thanksgiving dinner when, through a snowstorm, he saw helicopters descending into the basin. He and Cesar rushed up there on snowshoes and found ribbons and survey sticks everywhere.

Cesar jumped the claim, filed for it himself, and proved it up under the 1872 Mining Act’s “Prudent Man” language, which states that a claim is viable if it appears “a prudent man” could make a living from it.

What Prudent Man would give his life over to activism and the wilderness in the way that Cesar has? And yet, the claim stuck; he was deemed, or believed, to be a Prudent Man. Rumors swirl that he was offered a million dollars for it—this to a man with a yard full of broken or near-broken Subarus—but instead Cesar passed the claim to the Cabinet Resource Group, an all-volunteer organization he helped to form, that has had to raise the dollars to renew the mineral claim each year.

Sadly, the Scotchman’s—at the time one of two unprotected areas the Kootenai National Forest deemed worth managing as wilderness in all of its 2.4-million acre management area—seemed sometimes to be going backwards, up for grabs under then-current Forest Plan proposals. A few rogue snowmobiles had been trespassing into the area, in violation of Forest Plan standards, and there had been indications that some were willing to reward such trespass by legalizing it, despite the fact that the Scotchman’s had received more comments in support of wilderness designation than any other roadless area in Montana. Even today, conservationists continue to try to have the area protected as designated wilderness.

Here’s a typical Cesar endeavor: In nearby rural Thompson Falls—the southern end of the Cabinets—the local community agreed to let a wood-fired, cogenerating electrical plant be permitted, believing it would be fed by overstocked, small-diameter, non-marketable fuels produced from the thinning of brush and saplings in the community. But once the permit was secured and the plant had been purchased, the permittee applied for an amendment allowing them to burn coal instead of slash. (The narrow valley was already in non-compliance with federal air-quality laws). The notice was posted in the local paper on September 11, 2001 and was never commented upon; no one in Thompson Falls even knew of the change.

But Cesar noticed, and he helped the community organize. In addition to being exposed to excessive levels of mercury, particularly in light of the almost simultaneous relaxing of such standards by the second Bush administration, residents would have been exposed to tons of fly-ash, a product which, coincidentally, a proposed mine, the Rock Creek, less than thirty miles away, would need in great supply for their planned experimental mixing into the tailings pit. The permit was issued anyway, though the plant finally stopped burning coal in 2013. But at least one person spoke up. And at least other communities learned not to be tricked in this manner again.

In so many ways, the Cabinet-Yaak ecosystem seemed always to be the world-in-a-nutshell, the ground zero of all environmental matters, from corporate asbestos liabilities (the world’s largest asbestos mine once existed here) to endangered species attacks, and from wilderness issues to mining precedents and forest management abuses. It seemed to be a magical wellspring of challenge and yet also opportunity, destruction and yet creation, and Cesar was everywhere in it.

He fought a $68 million boondoggle proposal to pave a dirt road through the mountains, along which only two residents lived year-round. He was part of a citizens’ committee dedicated to recovering the grizzly population in the Cabinet-Yaak ecosystem. He participated weekly in the all-critical Forest Plan Revision meetings, which would help determine the next fifteen years of management direction for not just the Kootenai National Forest but the neighboring Idaho Panhandle National Forest as well.

Another interesting one-man Cesar fight involved the Revett Mining Company, which had bought the old, nearly played-out Troy mine. When copper prices dipped, the mine had closed a few years prematurely and left town—another of many economic yo-yos in the region. On the company’s way out of town, rumor had it they had buried some mysterious barrels of waste in their tailings impoundment. Cesar heard the rumor and chased it to ground. Revett denied there were any barrels. Cesar and the Cabinet Resource Group scraped up enough money to run a ground-penetrating radar survey and found about thirty barrels hidden within the tailings.

Oh, those barrels, the company said. Um, those barrels contain floculant, a harmless de-greaser. Perhaps to calm people down, the company did a water quality survey in a nearby creek, three miles away. No trichloroethylene here, they proclaimed.

Who said anything about trichloroethylene?

A check of manifest statements of trichloroethylene shipped into the mine, versus that accounted for, revealed a pretty significant disparity—enough for thirty barrels.

The last time I saw Cesar was in a meeting. He had taken a break to use the phone and was on two calls at once—one for the Cabinet Resource Group, the other for the Montana Wilderness Association. His back had gone out, and he was in pain. He looked stressed but steadfast. After the meeting, we visited a little, as ever, about the Scotchman’s and about Rock Creek. He informed me that some new activists in the region had learned a lesson from the original Prudent Man and had secured claims on a checkerboard of patents lying between the proposed Rock Creek mine and the highway: in effect, ringing and surrounding the proposed mine, as if holding it under siege.

Cesar grimaced as his back seized with a spasm, then released. He finished his coffee, grabbed his briefcase, and was out the door.

Contributors

Many talented individuals are featured in the West Marin Review. Please click below for this volume’s contributors.

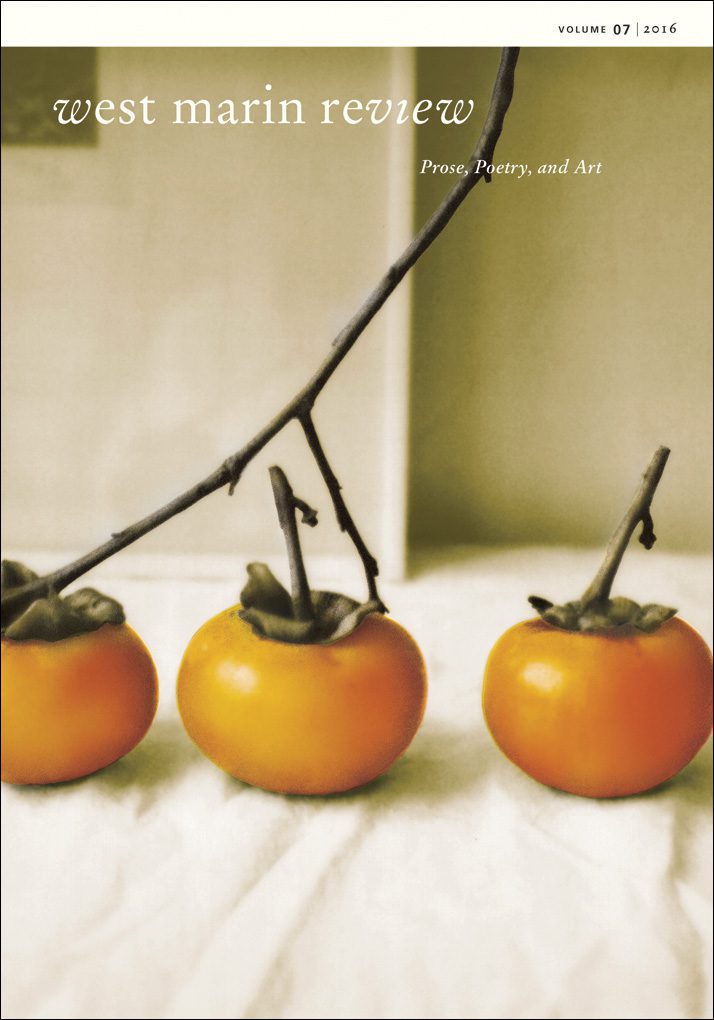

- FRONT COVER

- Noreen Rei Fukumori Fuyu Kaki

- BACK COVER

- Julia Edith Rigby Tomales Calf

- PROSE

- Blair Fuller Grand Central Station

- J. C. Stock Bird Standing on Water

- Rick Lyttle Unorganized Sports

- Vicki DeArmon A Mother’s No

- Stephanie E. Dickinson Emily and the Dynamite

- Alvin Duskin The Red Arrow

- Elaine Elinson Bringing the Grape Boycott to England

- Rick Bass The Prudent Man

- Molly Katzman When It Stops Raining We Sleep Beneath the Stars

- Rosaleen Bertolino The Burned Hill

- G. David Miller Our Family Farm

- Claire Peaslee Colophon

- POETRY

- Jody Farrell Ode to the First Blackberry of Summer

- Keith Ekiss Miss Maria’s New Dress

- Pamela Manché Pearce Ocean View, Hotel Nacional de Cuba

- Anuja Mendiratta Brasil Vignettes

- Roy Mash Revolving Sunglass Display

- Hiroki Coyle The Treasure

- Gerardo Loza Where I’m From

- Heather Quinn Mindspill: a Paradelle

- Agnes Wolohan von Burkleo Now I Am an Old Woman

- Dave Seter Mission Blues

- Gina Cloud night poem

- Dale Pendell Sunset

- Larry Ruth South Fork of the Kings River

- Cathryn Shea The Chill of Grace

- Claire Blotter California Wild Flower Tonic

- Anna Gold “Will You Miss This?”

- Mary Winegarden Untitled

- ART + ARTIFACT

- Ashley Teodoro Seal

- Adam Shemper On the Day of Our Engagement, Motel Inverness Boardwalk, Tomales Bay

- Jenifer Kent Wave and Transit

- Mariana Smith The Seed of an Idea

- Nancy Stein Wave 43

- Rebecca Czapnik So Little, So Much

- Brooke Holve mtlaugwalkcut_5

- Sophia Dixon Dillo Appearance I and Appearance III

- Noreen Rei Fukumori Backyard Fruit

- Gabriel Schillinger-Hyman Marine Study, Chimney Rock

- Topaze “t.c.” Moore Bestiary #1 and Quagga Stallion and Foal

- Sherri Paul The Treasure Hunter

- Patricia Thomas Fog

- Anne Faught URSA

- Julia Edith Rigby Tomales Calf

- Jacqueline Mallegni Haiku

- Vincent Dion Untitled #37

- Sage Rossman Two Trees

- Shirley Salzman Periodic Art of the Elements

- Theodora Varnay Jones CP-X

- Susan Putnam Untitled #244

- Eileen Puppo Seasonal Shock

- Wendy Schwartz Rich Readimix

- Bob Kubik Morning Coffee

- Adah Pinchuk Hyman Estero in Blue and Tomales Bay, Low Tide

- Kathleen Goodwin Homage to the Half Tree

- Andrew Thompson Warning: Bees

- Charles Eckart View from the Bicycle

- Caitlin McCaffrey Domed Nest with Pantry Chambers

- Catherine J. Richardson Caspian

- D. L. Woerner Joan’s Falcon

- Lisa Piazza Leaf #3

- Lorraine Almeida Growth in the Desert

- Isis Hockenos We, the Milked III

- Jon Langdon Asters in Starlight

- Thomas D. Joseph Tennessee Valley Beach

- Mark Ropers Point Lobos