I Be Loving My Neighbor’s Wife

G. David Miller

I agreed to meet with Jim McPhearson at the Old Ebbitt Grill for a late lunch. We hadn’t been in touch for years, ever since I quit the government and moved to California. The Old Ebbitt was an odd choice, made perhaps more out of nostalgia for the old days than for its food or promise of a quiet conversation. One block from the White House, it had always been a bit louche—but now it was overrun by tourists in shorts taking up excessive space and decibels, and holding cell phones at arm’s length, snapping that requisite selfie for someone somewhere.

Jim and I had worked together in Afghanistan in the mid-’70s herding an unruly pack of Peace Corps volunteers recruited and trained to teach English in remote villages in the Hindu Kush. Why anyone thought a large presence of young, eager Americans with a can-do spirit would win the hearts and minds of the recalcitrant tribes of Pashtuns, Tajiks, Hazaras, Uzbeks, Turkmen, and Balochs was a mystery then and now.

We moved to a table way in the back that was a bit quieter and began to reminisce about Afghanistan’s peaceful decade when Kabul was a stop along the road for world travelers heading east toward India. After a dozen oysters and several cold drafts, the conversation came around to Sebastian Fielder, one of those rare Peace Corps volunteers who had studied Farsi and Russian in college. I remember him telling me that he chose to come to Afghanistan because of the “sumptuous buffet of languages.” After going through training as an English teacher, Sebastian disappeared from my radar. He had been assigned to a small school in a remote village far from the reach of modern transport in a valley of the mountains of Paktia province.

After we ordered another round, Jim began his story about Sebastian.

“As you remember, the volunteers that concerned us most were the ones we heard from continually. They either had problems, complaints, or a need for stroking or approbation that consumed the time of our limited staff. There were always a few who couldn’t hack it and had to go home. Conditions were pretty rough. Those we heard from the least we considered to be our best volunteers. Fielder was one we heard from the least.

“We knew he was okay because he received and cashed his monthly stipend at the local post office in Lazah, about a half-hour walk from his village. And, once in every six months, he received and completed the standard bureaucratic form that served our need to calculate the Peace Corps’ contribution to American foreign policy goals. It was not until the late fall, when all volunteers were to show up at the annual retreat in Jalalabad, that we began to be concerned. He never came.

“A few days after the meeting, I took one of our four-wheel-drive vans to go check up on him. I had never been to his village before, and let me tell you, it was not easy to find. By early afternoon, on the road between Chamkani and Gardez, a light snow had begun to fall, turning the dirt road into a muddy, icy slush. I was lucky to make fifty kilometers per hour. And, of course, there were no road signs. It was nearing nightfall when I reached a chaikhana next to an old sign indicating that the intersection for Lazah was yet another forty-five kilometers. I felt it prudent to stop and spend the night there.

“Inside, steam from the giant samovar brought the temperature up to just about bearable with a coat on. I ordered some samosas and two pots of tea. As you remember, we used one pot to wash the tea cup. I then spread my sleeping bag on a charpoy and crashed into a deep sleep.

“In the morning, the sun was out and I continued on. I made it to Lazah in the middle of the day and, after getting directions, proceeded by foot to Sebastian’s village. After a half hour, with one enquiry at the small store, I found where he lived. The modest one room with latrine and kitchen in the back was constructed of the usual mud-brick and mortar. It was enclosed within a larger compound that had a covered well in the courtyard shared by several households. The door was open, so I went inside and waited for him to come home.

“While I was waiting, a Pashtun, bearing the usual black beard and dressed in baggy peron tambon and the pakol hat, arrived outside the window. He was carrying his gun with the requisite bandolier of bullets strung across his chest. He pushed the window open and sternly said to me in clear English, ‘Fuck you.’ He then walked away. As you can imagine, I found that rather unnerving.

“However, my disquiet was somewhat relieved when, shortly after that incident, Sebastian cheerily popped in the door and gave me a welcoming hug.

“We stretched out next to a charcoal brazier amidst piles of hand-woven woolen cushions and carpets and began to talk. I felt I had to share the recent incident of the face in the window. Sebastian smiled broadly and told me that the frightening fellow in question was Baraat, his housekeeper. As it turned out, Sebastian had introduced the phrase ‘fuck you’ to the denizens of his village as a friendly American salutation. Sebastian’s skill as an ambassador of American culture was borne out as we later strolled about the village exchanging this warm greeting with neighbors in a spirit of good cheer.

“As we talked, Baraat brought us tea, and to my relief, left without further pleasantries. It was then that I broached the subject of Sebastian’s failure to attend the annual meeting. ‘I was planning to be there,’ he told me. ‘In fact, I’d been putting aside a considerable sum each month from my postal draft for travel all around Afghanistan and neighboring countries—there’s little need for me to spend much of it in this village. I kept it in the ceiling.’ He pointed to the straw matting above. ‘Last month, I reached up through the straw for my cache to take out enough for travel to Jalalabad. I discovered that rats had crawled in and chewed it all up to make a nest. So it goes for my travel plans.’

“Sebastian insisted I sleep at his house and attend his English class in the morning, and I readily agreed. Baraat brought in dinner, added wood to the stove, and left us without speaking.

“We talked into the evening. Sebastian spoke about being a part of and apart from the intense life of the village, with no privacy except in his room. I sensed his relief in having me to talk to. By midnight, I was curled up by the stove and lay there listening to the silence, which was broken frequently by the distant howl of wolves, or dogs.

“The next morning, as I entered the one-room, mud-brick schoolhouse, boys and girls stood up stiffly and remained standing until Sebastian signaled them to sit. He then put them through their paces for me. Frankly, I was not prepared for it. In all the years I have observed English taught as a foreign language, I never saw anything quite like this.

“The students had in their possession only one verb: to be; as in I be, you be, he be, we be, they be. So: I be eating, I be sleeping, I be going. Past and future were handled by I be eating yesterday or I be happy you be coming tomorrow. I found this truly remarkable, since he managed to bring the communication skills of these students far beyond what I had seen in classes taught elsewhere over the same duration.

“Later, walking back to my van in Lazah, passing an occasional pedestrian who offered me a friendly, ‘Fuck you,’ I realized that Sebastian had infected the entire community with jive talk. Sebastianisms. Often I wondered if he had gone too far. Volunteers could easily step over the edge of what is appropriate in a highly traditional society.

“I didn’t hear from him for another twelve months, except to receive his semi-annual report. Then one day I received a letter from him asking to extend his time of service beyond the usual two years. Although such a request was not entirely unusual, it did not occur often. I thought I should check in on him again.

Contributors

Many talented individuals are featured in the West Marin Review. Please click below for this volume’s contributors.

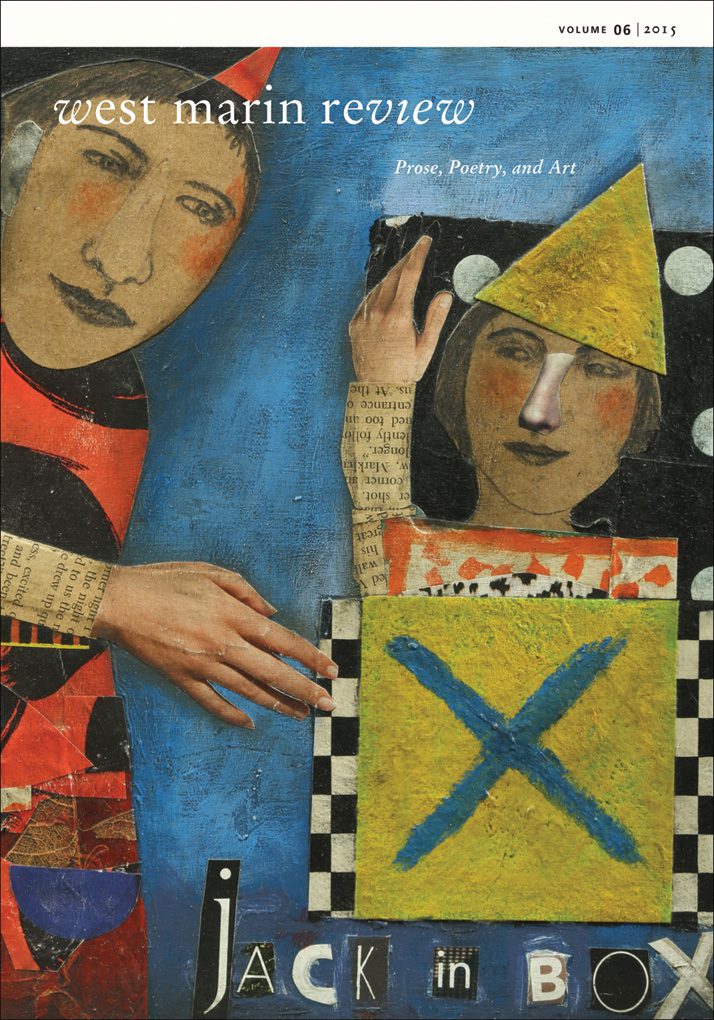

- Cover

- Marsha Balian Jill

- Prose

- Frances Lefkowitz Two Very Short Stories

- Sabine Hoskinson The Sespe

- Jon Langdon Red Rocker

- Jennifer Kulbeck Farallon Stories

- Michael Taylor Stunts

- Denise Parsons The Rancher Whispered

- Hal Ober From Old Hatch’s Almanac

- G. David Miller I Be Loving My Neighbor’s Wife

- Chris Reding Flying

- Betty Davidson The Complexity of the Sparrow

- Robert Kroninger Japs Not Wanted in Winters

- Susan Starbird Commuting in the Valley of Shadows

- Elisabeth Ptak Charles Dickens and Ferguson

- Poetry

- Tobi Earnheart-Gold Spring and Boredom

- Larry Ruth Light

- Scott Mossman The Olives of Olive Drive

- Roy Mash La-Z-Boy

- Heather Altfeld Indian, Wild (Ishi)

- Erin Rodoni Because There Is Loss

- Jody Farrell After Wendell Berry’s Window Poems

- Jed Myers Close to the Earth

- Barbara Finkelstein Return to Sinkyone

- Jocelyn Mata ¡Mi día en México!

- Catlyn Fendler July 31, A Meditation

- Gary Thorp Franz Kafka Dreams of Yosemite

- Lucas Benjamin Phenology

- Kaitlin Deasy The Letter

- Sierra Sabec The Origin of a Piano

- Elizabeth Herron As Light Escapes

- Jan Dederick Help Me Out, Billy

- Madeleine S. Butcher AWESOME

- Art + Artifact

- Paola Martin Canada Goose

- Leslie Allen Clear Spring Trough Above the Pacific,Valley Ford and Spaletta Ranch Barns, Valley Ford

- Elizabeth Sher Arbres arrencats d’ametles (Uprooted Almond Trees)

- Mary Siedman Highway One Trees and Magnolia

- Eva Bell Calla Lily

- Natalie Chavarria, Izabella Guiterrez, and Viviana Villalobos Gonzalez Sunflowers

- Eytan Schillinger-Hyman Serengeti Solitude

- Peter Connors Pacific Marine Algae

- Thomas Wood Northern Point Reyes Peninsula & Bodega Head

- Charles Hoehn West Bay

- Linda Weyl Old Barn on “101”

- Theodore D. Echeverria Poppies Celebrate the First Rains

- Charles Eckart On the Mesa—Point Reyes

- Bob Kubik Good Morning

- Jacqueline Mallegni Wabi-Sabi Basket

- Adah Pinchuk Hyman October Sunset, Tomales Bay

- Vanessa Waring Everyone’s Invited

- Michelle Chayes Mermaid

- Terry Murphy Cat Nap

- T.C. Moore Hay Nets

- Judy Levit Unanswered Questions

- Anne Faught Journal Entry

- Mary K. Shisler Turnips… and Onions…

- Ward Walkup III summer, fall, winter… SPRING!

- Jenny Long Walk

- Susan Putnam Untitled #226

- Isela Carreras Different

- Ashley Eva Brock Shoe Creature

- Ido Yoshimoto Untitled from the Series Astral Planes

- Micheleen Tolson Cyanotype Leaf

- Sawyer Rose Metamorphosis and Costanoa Coral

- Mark Ropers Kite at Stinson Beach

- Music

- Agnes Wolohan von Burkleo Lullaby for Seamus