DANCING

Robert Hass

The radio clicks on—it’s poor swollen America,

up already and busy selling the exhausting obligation

of happiness while intermittently debating whether or not

a man who kills 50 people in five minutes

with an automatic weapon he has bought for the purpose

is mentally ill. Or a terrorist. Or if terrorists

are mentally ill. Because if killing large numbers of people

with sophisticated weapons is a sign of sickness—

you might want to begin with fire, our early ancestors

drawn to the warmth of it—from lightning,

must have been, the great booming flashes of it

from the sky, the tree shriveled and sizzling,

must have been, an awful power, the odor

of ozone a god’s breath; or grass fires,

the wind whipping them, the animals stampeding,

furious, driving hard on their haunches from the terror

of it, so that to fashion some campfire of burning wood,

old logs, must have felt like feeding on the crumbs

of the god’s power and they would tell the story

of Prometheus the thief, and the eagle that feasted

on his liver, told it around a campfire, must have been,

and then—centuries, millennia—some tribe

of meticulous gatherers, some medicine woman,

or craftsman of metal discovered some sands that,

tossed into the fire, burned blue or flared green,

so simple the children could do it, must have been,

or some soft stone rubbed to a powder that tossed

into the fire gave off a white phosphorescent glow.

The word for chemistry from a Greek—some say Arabic—

stem associated with metal work. But it was in China

2,000 years ago that fireworks were invented—

fire and mineral in a confined space to produce power—

they knew already about the power of fire and water

and the power of steam: 100 BC, Julius Caesar’s day.

In Alexandria, a Greek mathematician produced

a steam-powered turbine engine. Contain, explode.

“The earliest depiction of a gunpowder weapon

is the illustration of a fire-lance on a mid-12th century

silk banner from Dunhuang.” Silk and the Silk Road.

First Arab guns in the early 14th century. The English

used cannons and a siege gun at Calais in 1346.

Cerigna, 1503: the first battle won by the power of rifles

when Spanish “arquebusters” cut down Swiss pikemen

and French cavalry in a battle in southern Italy.

(Explosions of blood and smoke, lead balls tearing open

the flesh of horses and young men, peasants mostly,

farm boys recruited to the armies of their feudal overlords.)

How did guns come to North America? 2014,

a headline: DIVERS DISCOVER THE SANTA MARIA.

One of the ship’s Lombard cannons may have been stolen

by salvage pirates off the Haitian reef where it had sunk.

And Cortes took Mexico with 600 men, 17 horses, 12 cannons.

And LaSalle, 1679, constructed a seven-cannon barque,

Le Griffon, and fired his cannons upon first entering the continent’s

interior. The sky darkened by the terror of the birds.

In the dream time, they are still rising, swarming,

darkening the sky, the chorus of their cries sharpening

as the echo of that first astounding explosion shimmers

on the waters, the crew blinking at the wind of their wings.

Springfield Arsenal, 1777. Rock Island Arsenal, 1862.

The original Henry rifle: a 16-shot .44 caliber rimfire

lever-action, breech-loading rifle patented—it was an age

of tinkerers—by one Benjamin Tyler Henry in 1860,

just in time for the Civil War. Confederate casualties

in battle: about 95,000. Union casualties in battle:

about 110,000. Contain, explode. They were throwing

sand into the fire, a blue flare, an incandescent green.

The Maxim machine gun, 1914, 400–600 small-caliber rounds

per minute. The deaths in combat, all sides, 1914–1918

was 8,042,189. Someone was counting. Must have been.

They could send things whistling into the air by boiling water.

The children around the fire must have shrieked with delight.

1920: Iraq, the peoples of that place were “restive”

under British rule and the young Winston Churchill

invented the new policy of “aerial policing” which amounted,

sources say, to bombing civilians and then pacifying them

with ground troops. Which led to the tactic of terrorizing civilian

populations in World War II. Total casualties in that war,

worldwide: soldiers, 21 million; civilians, 27 million.

They were throwing sand into the fire. The ancestor who stole

lightning from the sky had his guts eaten by an eagle.

Spreadeagled on a rock, the great bird feasting.

They are wondering if he is a terrorist or mentally ill.

London, Dresden. Berlin. Hiroshima, Nagasaki.

The casualties difficult to estimate. Hiroshima:

66,000 dead, 70,000 injured. In a minute. Nagasaki:

39,000 dead, 25,000 injured. There were more people killed,

100,000, in more terrifying fashion in the firebombing

of Tokyo. Two arms races after the ashes settled.

The other industrial countries couldn’t get there

fast enough. Contain, burn. One scramble was

for the rocket that delivers the explosion that burns humans

by the tens of thousands and poisons the earth in the process.

They were wondering if the terrorist was crazy. If he was

a terrorist, maybe he was just unhappy. The other

challenge afterwards was how to construct machine guns

a man or a boy could carry: lightweight, compact, easy to assemble.

First a Russian sergeant, a Kalashnikov, clever with guns

built one on a German model. Now the heavy machine gun,

the weapon of European imperialism through which

a few men trained in gunnery could slaughter native armies

in Africa and India and the mountains of Afghanistan,

became “a portable weapon a child can operate.”

The equalizer. So the undergunned Vietnamese insurgents

fought off the greatest army in the world. So the Afghans

fought off the Soviet army using Kalashnikovs the CIA

provided to them. They were throwing powders in the fire

and dancing. Children’s armies in Africa toting AK-47s

that fire 30 rounds a minute. A round is a bullet.

An estimated 500 million firearms on the earth.

One hundred million of them are Kalashnikov-style semi-automatics.

They were dancing in Orlando, in a club. Spring night.

Gay Pride. The relation of the total casualties to the history

of the weapon that sent exploded metal into their bodies—

30 rounds a minute, or 40, is a beautifully made instrument,

and in America you can buy it anywhere—and into the history

of the shaming culture that produced the idea of Gay Pride—

they were mostly young men, they were dancing in a club,

a spring night. The radio clicks on. Green fire. Blue fire.

The immense flocks of terrified birds still rising

in wave after wave above the waters in the dream time.

Crying out sharply as the French ship breasted the vast interior

of the new land. America. A radio clicks on. The Arabs,

a commentator is saying, require a heavy hand. Dancing.

Contributors

Many talented individuals are featured in the West Marin Review. Please click below for this volume’s contributors.

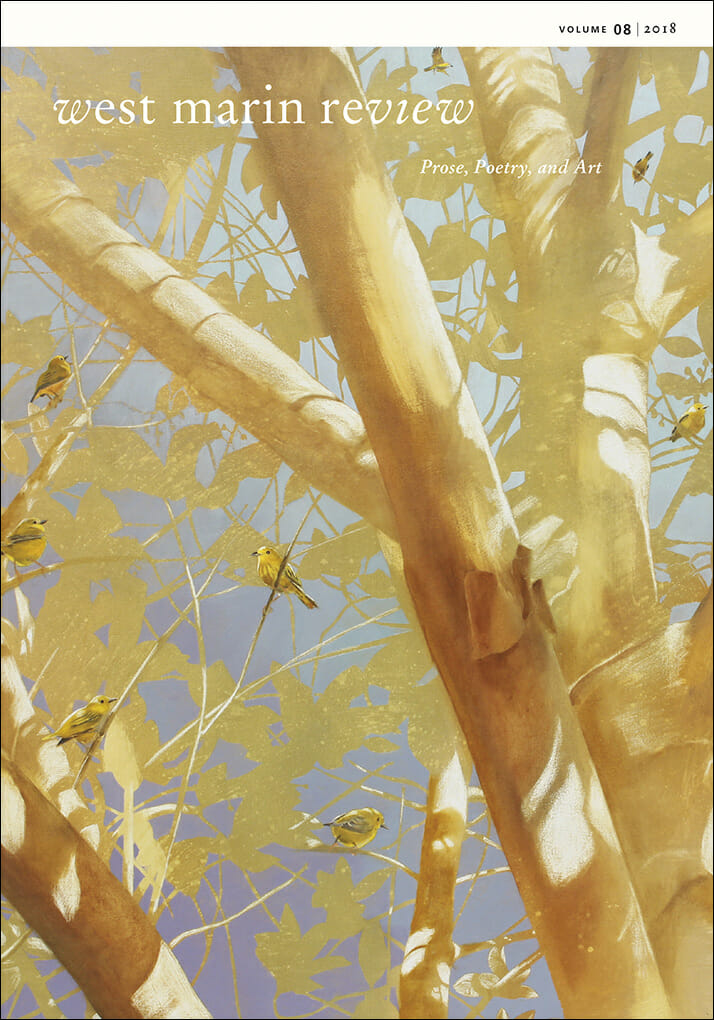

- FRONT COVER

- Kay Bradner Ten Birds

- BACK COVER

- Cathy Rose Balance

- PROSE

- Jackie Garcia Mann Bolinas Bound

- Michael Sykes Leaving for Italy

- Dave Stamey To Steelhead Lake

- Joan Thornton Two Short Stories

- Barbara Heenan On Religion: Oklahoma City

- G. David Miller Prepare for Landing

- Kaitlyn Gallagher The Blows

- Cynthia Fontaine Reehl What It Takes

- Molly Giles Next Time

- Paul Strohm Masculinities

- Brooke Williams Post-Election Walkabout

- POETRY

- Tobi Earnheart-Gold Untitled

- Mary Winegarden Between Birth and Song

- Ariel Wish Through Motions

- Nancy Cherry All My Biographies Are Lies

- Stephen Ajay Giving

- Karen Benke Spring Cleaning

- Lisa Piazza Here

- Barry Roth Henry Evans Poppies

- Thomas Hickey Monk’s Empty Eye

- Satchel Trivelpiece Oh, Animals

- David Swain Dead Reckoning

- Robert Hass DANCING

- Deborah Buchanan A Bowl’s Circumference

- Prartho Sereno Emergency Lock-Down Drill

- Dave Seter Douglas Iris

- Judy Brackett Swimming Through Summer

- Gina Cloud Ken

- ART + ARTIFACT

- Kay Bradner Ten Birds

- Christa Burgoyne Small Barn and Late Afternoon “C” Street

- Lissa Nicolaus Country Road

- Kimberly Carr Harmon Wooded Gate

- Emmeline Craig Living on the Edge

- Matthew Polvorosa Kline Tule Elk at Dawn, Point Reyes National Seashore

- Elizabeth Gorek Forgotten Summer

- Susan Hall California Twilight

- Sandy White Roy’s Redwoods

- Jaune Evans Fog Heaven

- Isis Hockenos Side Street Chickens #1 & #2

- Caitlin McCaffrey Biggie’s Vision

- Marius Salone and Sofia Borg Young Red Onions

- Lily Andrews Hummingbird

- Susan Putnam Untitled #261

- Amanda Tomlin Laird’s Boathouse

- Jani Gillette You Wearing You

- Christel Dillbohner Iridescent Cloud

- Philip Bone Three Masks

- May Ta Somber Summer

- Toni Littlejohn Fire Under Ice

- Xander Weaver-Scull Arctic Peregrine Falcons

- Grace Nichols and Belle Nichols Southworth Letters from Bolinas

- Julia Edith Rigby Waste in Paradise

- Van Waring Coastal Cross Section

- Rich Clarke Kehoe Morning

- Johanna Baruch Enthymesis

- Michel Venghiattis Lili Marlene

- Glenn Carter Night of the Falling Flower/Lucid N13-2

- Sherrie Lovler Crossroads

- Mary Siedman Bolinas Beach

- Jon Ching Flowers in Her Hair

- Mark Ropers Bound for Kilkenney Beach

- Mary K. Shisler Wabi Sabi Tulips

- Richard Kirschman Bogside Remembered

- Patricia Connolly Late Afternoon at McInnis

- Bob Kubik Fox

- Cathy Rose Accept and Balance

- Anne Faught Coming Together